As Indonesia embarks on its energy transition, the country faces an investment requirement of approximately USD 988 billion to achieve Net Zero Emissions by 2060 (RUKN1, 2025). Such a scale of investment cannot be borne solely by the state budget (APBN2) and will require blended financing that combines public resources, private capital, and international funding. Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) are, therefore, a critical instrument to mobilize and de-risk private investment. Yet, despite this potential, World Bank data shows that renewable energy PPPs in Indonesia accounted for only 20% of total PPP investments between 2000–2020, underscoring a significant gap between regulatory ambition and implementation.

Regulatory Framework and Implementation Challenges

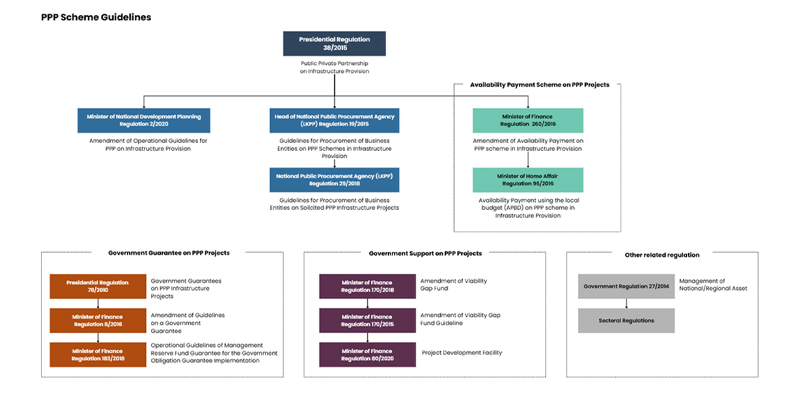

Indonesia’s PPP regulatory framework has evolved significantly, particularly following Presidential Regulation No. 38/2015, which introduced fiscal support mechanisms such as the Viability Gap Fund3 (VGF), Project Development Facility4 (PDF), availability payments, and government guarantees. The regulation also clarified institutional roles: Bappenas5 coordinates PPP planning and ensures project alignment with national development priorities, the Ministry of Finance manages fiscal support and contingent liabilities, KPPIP6 expedites priority projects, and Government Contracting Agencies (GCAs) serve as project sponsors.

Figure 1. Indonesia PPP Institutional and Regulatory Framework

However, implementation of PPPs for renewable energy projects continues to face structural barriers. GCA capacity to prepare feasibility studies and manage tenders remains uneven, standardized concession agreements and compensation clauses are lacking, and the Viability Gap Fund (VGF)—introduced in 2012 and strengthened under the 2015 PPP framework—has yet to be deployed for renewable energy projects, leaving high-cost RE initiatives without substantial capital support. At the same time, the Maximum Guarantee Limit7 (MGL) for 2018–2021 was set at IDR 1,178 trillion (6% of GDP), but by 2021 only 40–50% had been utilized, largely for non-renewable sectors (Ministry of Finance, 2021), highlighting the mismatch between fiscal capacity and RE financing needs.

In the energy sector, PPPs are heavily reliant on international sponsors with 66–68% of Independent Power Producer (IPP) projects are backed by foreign investors reflecting

dependency on external capital and expertise. Government support is concentrated in availability/performance payments (around 70%) and guarantees, while VGF allocations to energy projects are virtually zero (Asian Development Bank, 2020). Payment mechanism is highly dominated under government control, indicated by specific contractual mechanism (government offtake), with PLN acting as the sole buyer, which strengthens bankability for large projects but also creates fiscal exposure and contractual risk. Compounding these challenges, tariff caps on feed-in tariffs constrain project IRRs, while shorter PPA tenors increase investor risk premiums, resulting in fewer renewable projects advancing from pipeline to financial close.

International Benchmark: India’s Case Study

In contrast, India illustrates how clear regulation, fiscal support, and decentralization can catalyze renewable energy PPPs. The Vadodara Solar Rooftop PPP in Gujarat adopted a 25-year build–own–operate model in which the private sector financed, built, and operated rooftop solar systems, while the government provided rooftops, bankable PPAs, and VGF to offset upfront risks, with IFC8 ensuring transparency as transaction advisor. The project mobilized USD 8 million, delivered electricity to 9,000 people, and reduced 6,000 tons of CO₂ annually (IFC, 2015).

Beyond this case, India has consistently backed its policies with fiscal commitments, allocating over USD 1.8 billion in VGF between 2023–2025 for solar, offshore wind, and battery storage (MNRE9 India, 2024). This combination of substantial fiscal allocation and decentralized execution through state nodal agencies and the Solar Parks program has accelerated financial closure across the sector, highlighting that successful renewable energy PPPs require not just strong regulation and bankable PPAs, but also targeted fiscal support and empowered local institutions, areas where Indonesia continues to lag.

Recommendations for Strengthening Renewable Energy PPPs in Indonesia

- Enhance Regulatory Coherence and Long-term Certainty

Indonesia should adopt a unified Renewable Energy and PPP Framework Act to streamline overlapping mandates, clarify risk-sharing, and fiscal commitments. This will strengthen investor confidence while preserving flexibility for emerging technologies.

- Expand VGF Allocation for RE and Optimize Fiscal Space

Allocate targeted VGF for high-risk, socially vital RE projects, leveraging unused MGL to expand fiscal support. Complement with green sukuk and blended finance from Multilateral Development Banks to diversify funding and enhance project bankability.

- Strengthen Decentralization and Local GCA Capacity

Strengthen local GCAs by replicating the Solar Parks model, where subnational agencies lead project preparation and land provision. To bridge fiscal disparities between regions, the central government should provide matching grants, shared-risk funds, and technical assistance for less-capacitated provinces.